‘Blue’ is the name of a little detached house on a quiet residential street in an Ottawa neighbourhood known as Centretown. It’s the sixth in a row of seven houses built on spec in the go-go days following the arrival of the Canada Atlantic Railway in 1882.

The houses were identical and their construction was practical: they are narrow (16 feet) relative to their height and the pitch of the roof is extreme (more than 1:1); they are deep, ‘shotgun’ style, and feature a large front window on the ground floor to allow as much natural light as possible.

The ‘Seven Sisters’ were built all in a line and close to the street. Each of them was built towards one side of a lot 25 feet wide.

In my client’s case, the parking slip was less than 7 feet wide; a telephone pole on the property line adjacent to the sidewalk made access difficult. When you parked even a compact car in Blue’s driveway, the driver’s door was abreast of the front porch. There was barely enough space to get out of the car and after twice creasing her door my client decided to take action.

It was a temptation to take revenge on the offending porch and just saw off 18 inches, but that would have run afoul of official Ottawa.

Rebuilding presented another problem: the municipal right-of-way had advanced upon the house since the construction of the porch and the bottom step was now one foot over the line; an agreement over the encroachment would have to be negotiated with the city prior to any application for permit.

Meanwhile the old porch was sinking into the ground. But it was at least symmetrical. Replacing it with a shorter porch – option ‘A’- would not enhance Blue’s curb appeal. I proposed we explore other options.

All of the other ‘sisters’ but one had an exterior vestibule. Blue, like its siblings had an open interior plan and the abrupt loss of privacy every time you opened the front door was an offence. On a winter day you felt the rush of cold air as far back as the kitchen.

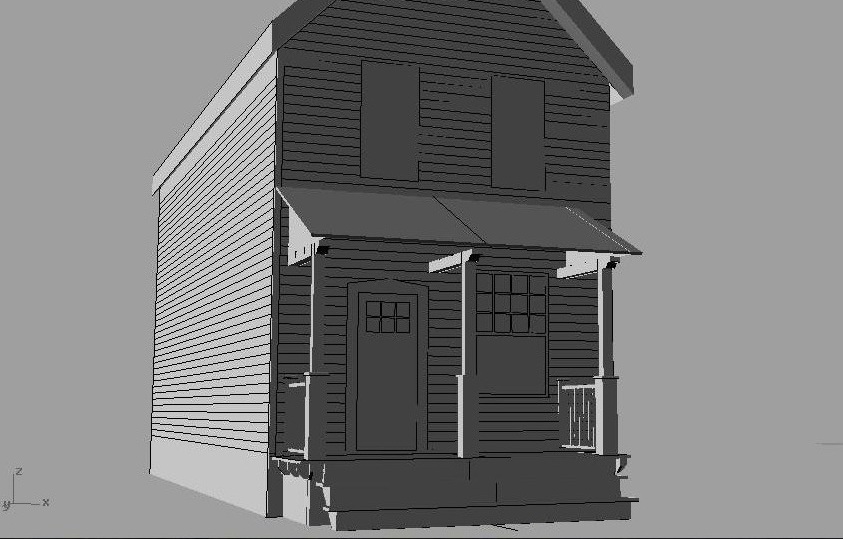

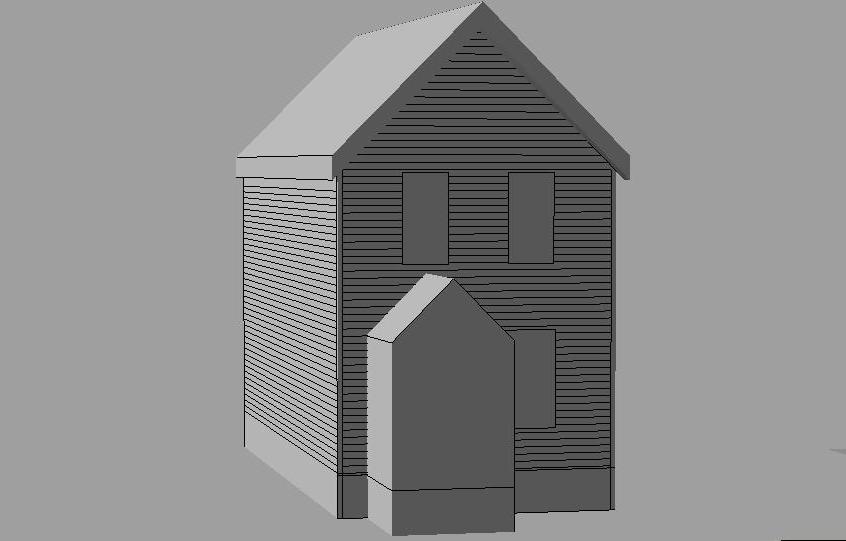

I created CAD models of an exterior vestibule with every style of roof: gable, flat, shed and hip. More than one person told me there was only one solution: to centre the vestibule on the door and upper window and mimic the slope of the roof, as illustrated below, right, and by the second house from the left, above. I saw this default solution as a caricature of the house in miniature and too small a vestibule to be practical.

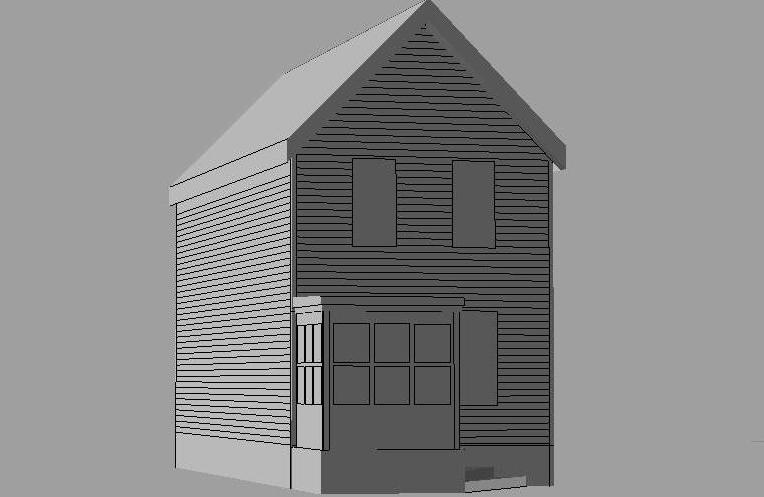

The limitation on the depth of the vestibule imposed by the municipal setback, and the space required for the swing of the inward-opening exterior door dictated a side entry, as shown (left, right) above.

But this deviated entrance was at odds with the overall plan of the house based on its dominant longitudinal axis. Nor did it provide much more space to welcome multiple guests. And it was not obvious how to reconcile a closed vestibule with a dissimilar roof with the existing façade of the house.

As the challenges and limitations of an enclosed exterior vestibule became obvious, an open portico emerged as the most practical alternative to the original porch.

An open structure would be intuited as adornment of the façade and its proportions would not have to follow the existing façade as closely.

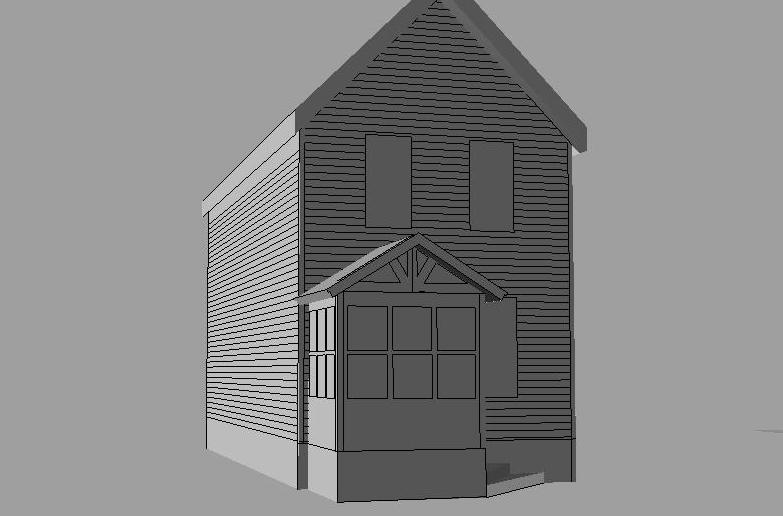

Architecturally, the façade of the house was a blank slate and I worked in a 1920’s Craftsman style whose emphasis on structure spoke to the expediency of the original design of the house.

I allowed myself free reign in designing the portico, gambling the house would normally be viewed from the sidewalk and that perspective would disguise the dissimilarity between the slopes of the portico roof and that of the house.

I made the portico large enough to assert itself over the plainness of the façade and I was obliged to make it disproportionately tall to avoid the roof intruding upon the oversize front window.

I regretted the loss of proportionality but the result nonetheless suited the proportions of the house; the separation of the deck and roof, both of which had classic proportions themselves, gave the portico a steampunk vibe. This was consistent with the contrast between the old house and its newly renovated interior which was unabashedly modern.

Of course the exterior portico did not address the problem of the lack of a proper vestibule. An interior vestibule would have occupied too much critical interior space. The solution was a ‘virtual’ vestibule, created by a partition wall adjacent to the door providing a social barrier and a windbreak for anyone in the living room nook on the other side.

The partition was rendered less intrusive by the incorporation of a salvaged window mounted in relief as if ‘found art’ on the interior of the wall, rendering the partition less opaque.

Demolition of the old porch went quickly. Excavation of the footings took a little longer: they were deep enough but the conditions of our permit obliged their replacement.

Raising the roof required coaxing the tree in the front yard away from the house towards a telephone pole with a block-and-tackle. Fortunately for us the tree moved and not the telephone pole.

Permit delays had shifted our initial August start date to late November. December thankfully was unseasonably mild but there was snow falling as I finished shingling the roof and replacing the last of the siding on the front of the house.

The new portico was to be the last improvement prior to putting the house up for sale. But Blue was not my client’s principal residence and she had taken such pleasure in its renovation she had begun to have second thoughts about giving up her Ottawa pied-à-terre. Blue was taken off the market after only a matter of days, with no immediate plans for its sale.

Inside Ottawa:

When the initial response of Ottawa’s permits department to my application was to prescribe vinyl clad aluminum railings and prefabricated roof trusses, I knew we were in trouble.

Ultimately, the department was convinced of the integrity of my roof structure, but only after it had been approved by a structural engineering firm. I was obliged to build a conventional deck structure, with the Craftsman structural elements serving only as wrapping for the underlying pressure-treated spruce and joist hangers.

These were minor annoyances. The real challenge to securing a permit for our modest but essential renovation was the encroachment. Although we were not seeking a variance any more significant than that of the neighbouring houses, its approval was by no means guaranteed.

It’s a story for another day, but in a nutshell, my impression of official Ottawa from my relations with many intelligent, conscientious municipal employees is that of a labyrinth of independent departments each of which has the capability of arresting the progress of a project and only one with the authority to grant final approval, that being reserved for one lone, shady figure deep in the city’s bureaucratic Heart of Darkness.

Who nonetheless approved our application. But by the time our building permit had been finally approved our early August start date had shifted to late November and I had already fabricated, pre-assembled and painted every component of the portico in a garage in Montreal.

The same day that I was informed our permit was waiting to be picked up at a service counter in Ottawa, I was loading the truck in light snow when I got a second call: Heritage Services had not approved our project. Approval of our application for permit hung in the balance once again.

A heartfelt appeal to Heritage Services fell upon a sympathetic ear but they would nonetheless have to take the time to study our project, once they had received our file. Their follow up came the following week: they were apologetic as our neighbourhood did not fall under their jurisdiction.

Blue Gets a Face-lift.

‘Blue’ is the name of a little detached house on a quiet residential street in an Ottawa neighbourhood known as Centretown. It’s the sixth in a row of seven houses built on spec in the go-go days following the arrival of the Canada Atlantic Railway in 1882.

The houses were identical and their construction was practical: they are narrow (16 feet) relative to their height and the pitch of the roof is extreme (more than 1:1); they are deep, ‘shotgun’ style, and feature a large front window on the ground floor to allow as much natural light as possible.

The ‘Seven Sisters’ were built all in a line and close to the street. Each of them was built towards one side of a lot 25 feet wide.

I got what you intend,bookmarked, very decent website.